Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

The domain: what is a theory of social cognition a theory of?

Social cognition:

cognition of

others’ actions and mental states

in relation to social functioning.

The question: Radical Interpretation*

How in principle could someone infer facts about actions and mental states from non-mental evidence?

What is the relation between an account of radical interpretation* and a theory of social cognition?

A theory of radical interpretation* is supposed to provide a computational description of social cognition.

Theories of radical interpretation*:

The Intentional Stance (Dennett)

Davidson’s Theory

The Teleological Stance & Your-Goal-Is-My-Goal

Minimal Theory of Mind

also an implicit theory associated with perception of emotion

Reciprocity

reciprocity

reciprocity

reciprocity

reciprocity

reciprocity

reciprocity

without escalation

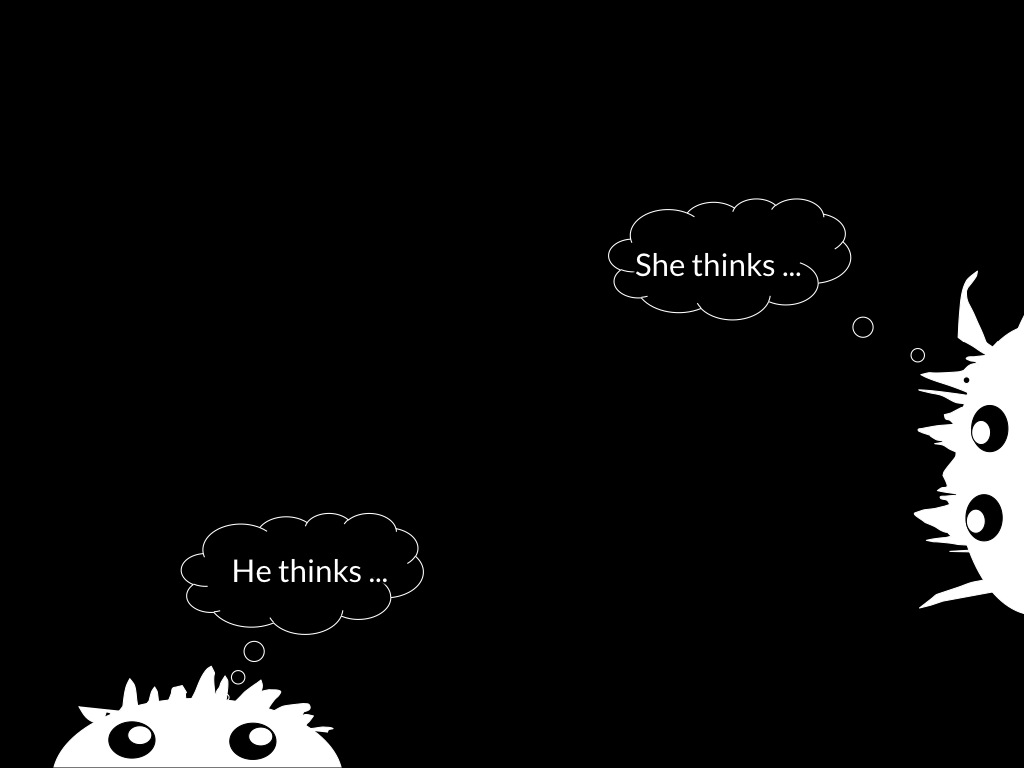

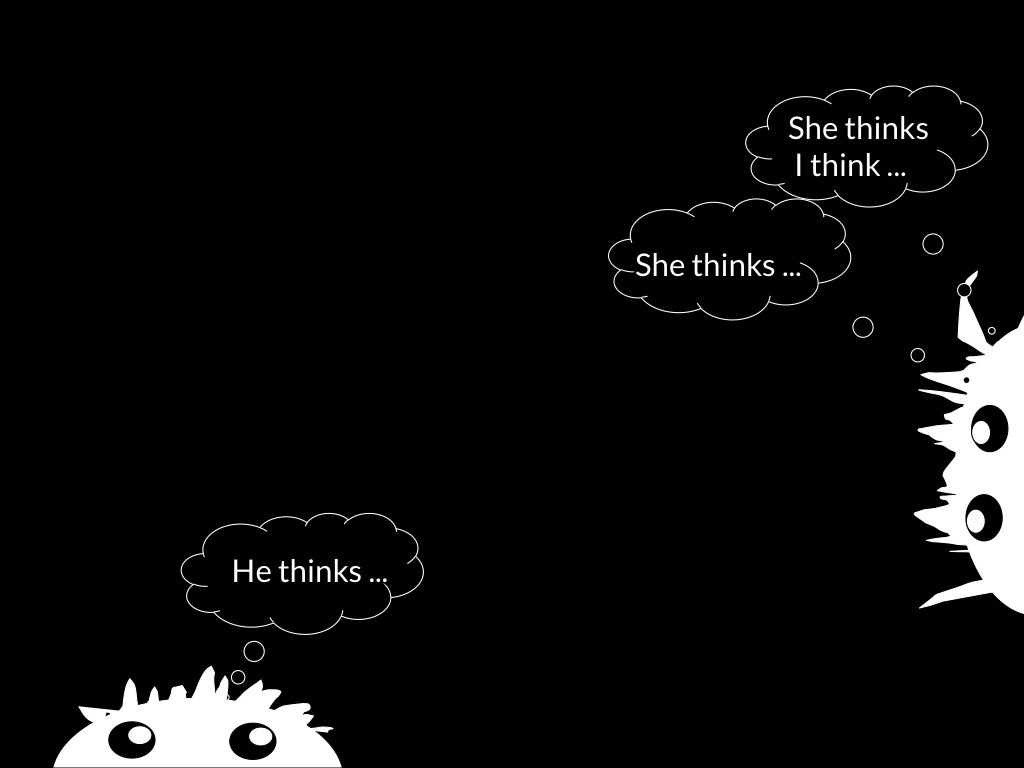

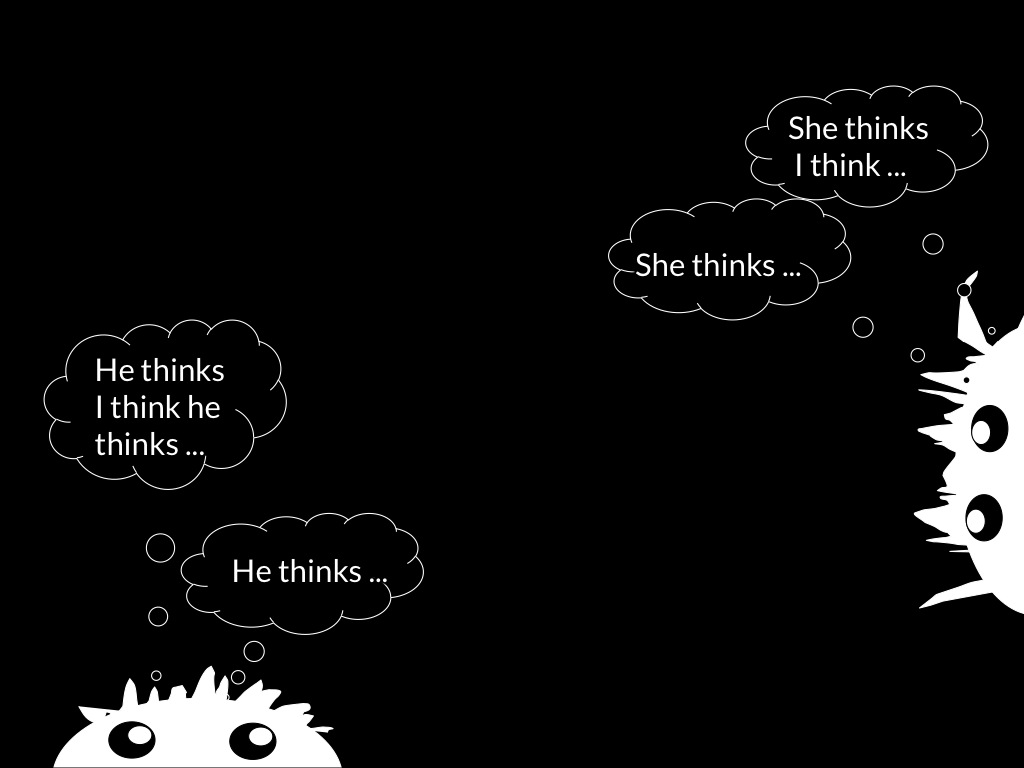

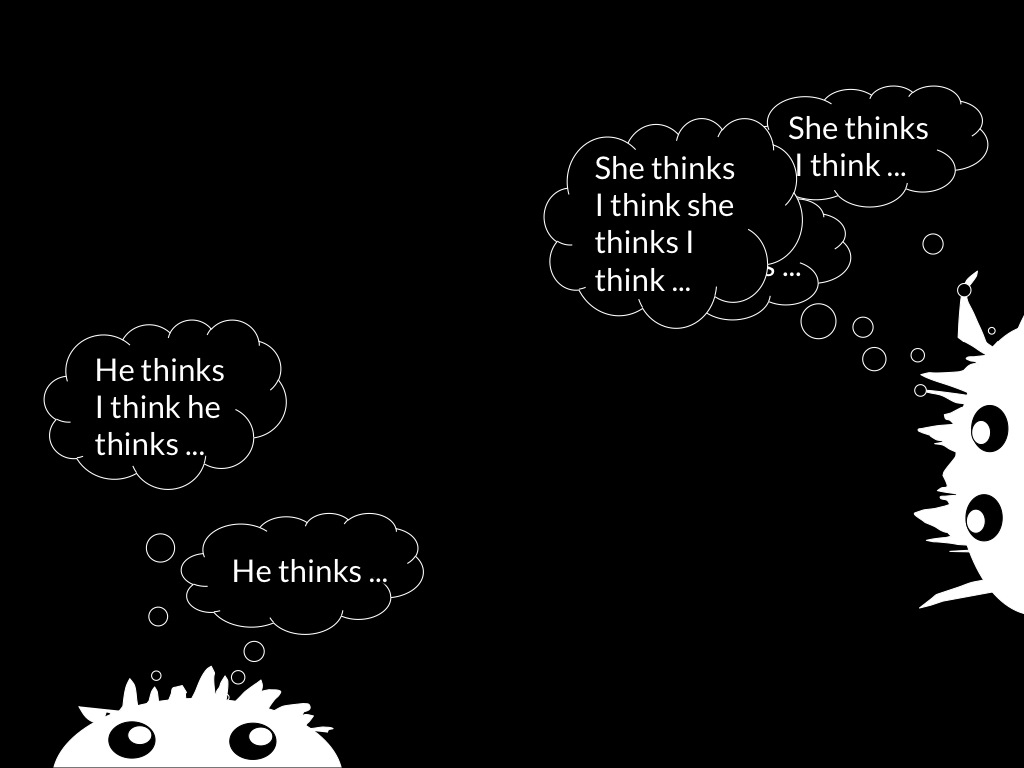

Could interacting interpreters be in a position to know things which they would be unable to know if they were manifestly passive observers?

Step 1: Which obstacle to knowledge?

Step 2: How?

Obstacle: opaque means impair goal ascription

e.g. pram -> bus; gorilla preparing nettles

e.g. tool use

‘an action can be explained by a goal state if, and only if, it is seen as the most justifiable action towards that goal state that is available within the constraints of reality’

Csibra & Gergely (1998, 255)

1. action a is directed to some goal;

2. actions of a’s type are normally means of realising outcomes of G’s type;

3. no available alternative action is a significantly better* means of realising outcome G;

4. the occurrence of outcome G is desirable;

5. there is no other outcome, G′, the occurrence of which would be at least comparably desirable and where (2) and (3) both hold of G′ and a

Therefore:

6. G is a goal to which action a is directed.

Obstacle: opaque means impair goal ascription

e.g. pram -> bus; gorilla preparing nettles

e.g. tool use

e.g. communicative actions

Could interacting interpreters be in a position to know things which they would be unable to know if they were manifestly passive observers?

Step 1: Which obstacle to knowledge?

Step 2: How?

Your goal is my goal

collective

Jack’s and Ayehsa’s actions are collectively directed to developing a vaccine for Zika

not collective

Ilsa and Ahmed’s actions are each individually directed to developing a vaccine for Zika

Those speakers collectively provide high fidelity reproduction.

Each of those speakers individually provides high fidelity reproduction

collective goal : an outcome to which our actions are collectively directed

joint action : an action with a collective goal

intuitive idea, not quite right

but: cues to joint action

Your-goal-is-my-goal

1. You are about to attempt to engage in some joint action or other with me.

2. I am not about to change the single goal to which my actions will be directed.

Therefore:

3. A goal of your actions will be my goal, the goal I now envisage that my actions will be directed to.

| teleological stance | your-goal-is-my-goal | |

| demands know means | ✓ | ✗ |

| demands can interact | ✗ | ✓ |

What about the problem of opaque means?

e.g. pram -> bus; gorilla preparing nettles

e.g. tool use illustrates inversion of demands

e.g. communicative actions

Could interacting interpreters be in a position to know things which they would be unable to know if they were manifestly passive observers?

A thesis about interaction and social cognition

Theories of radical interpretation*:

The Intentional Stance (Dennett)

Davidson’s Theory

The Teleological Stance & Your-Goal-Is-My-Goal

Minimal Theory of Mind

also an implicit theory associated with perception of emotion

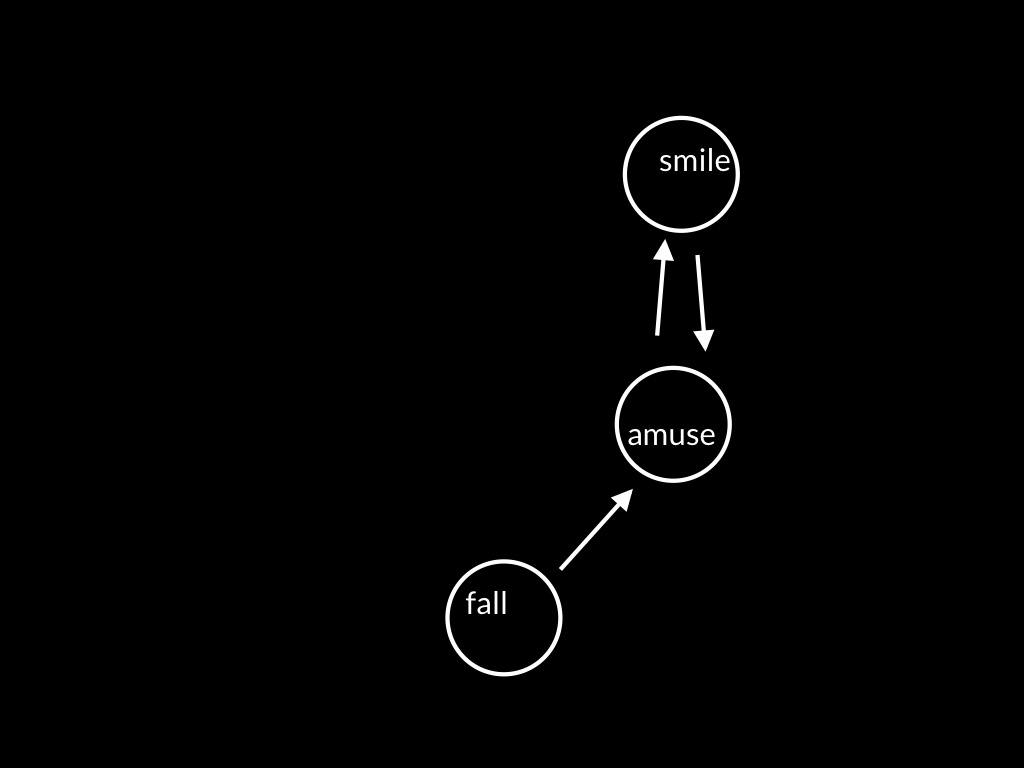

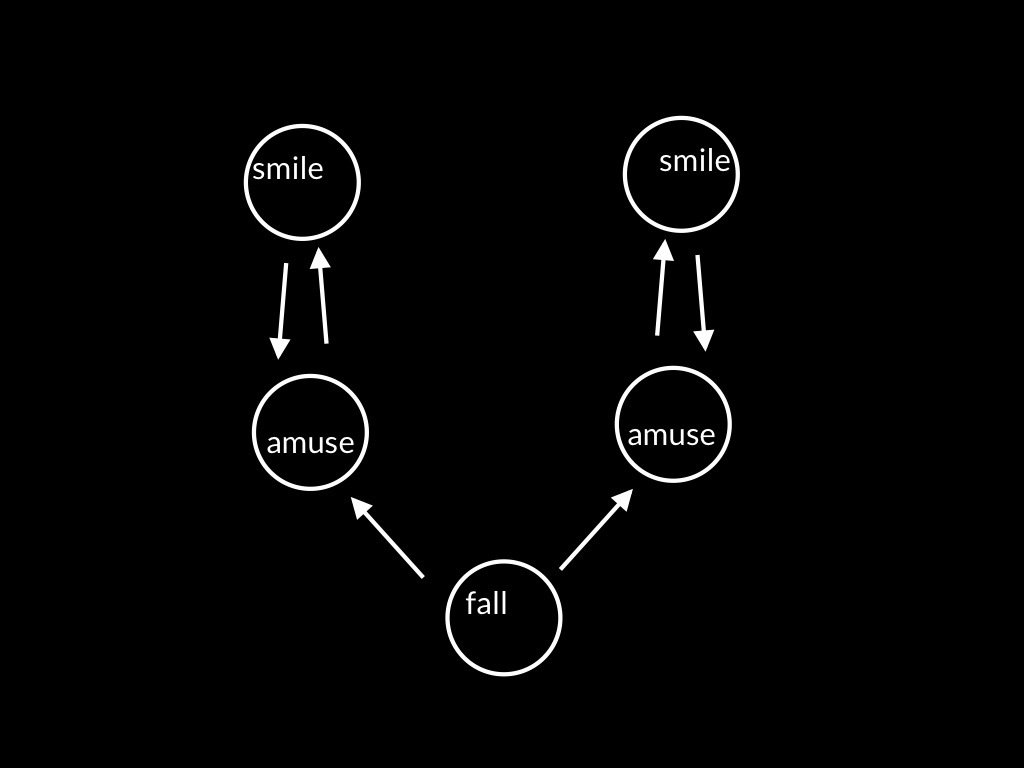

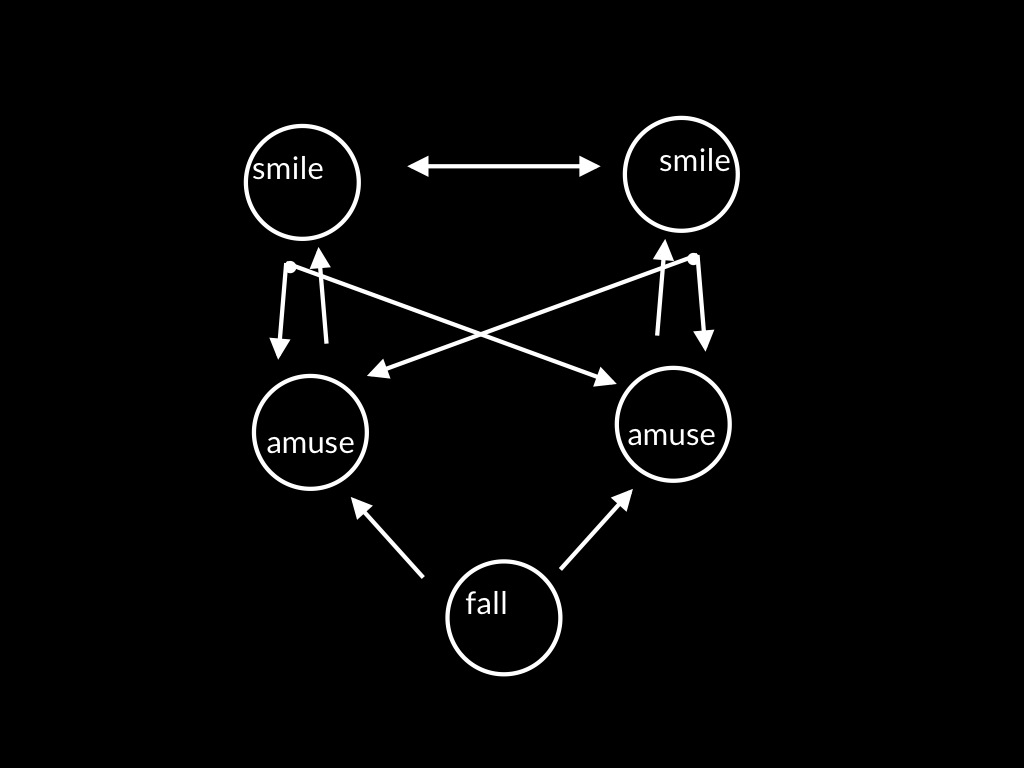

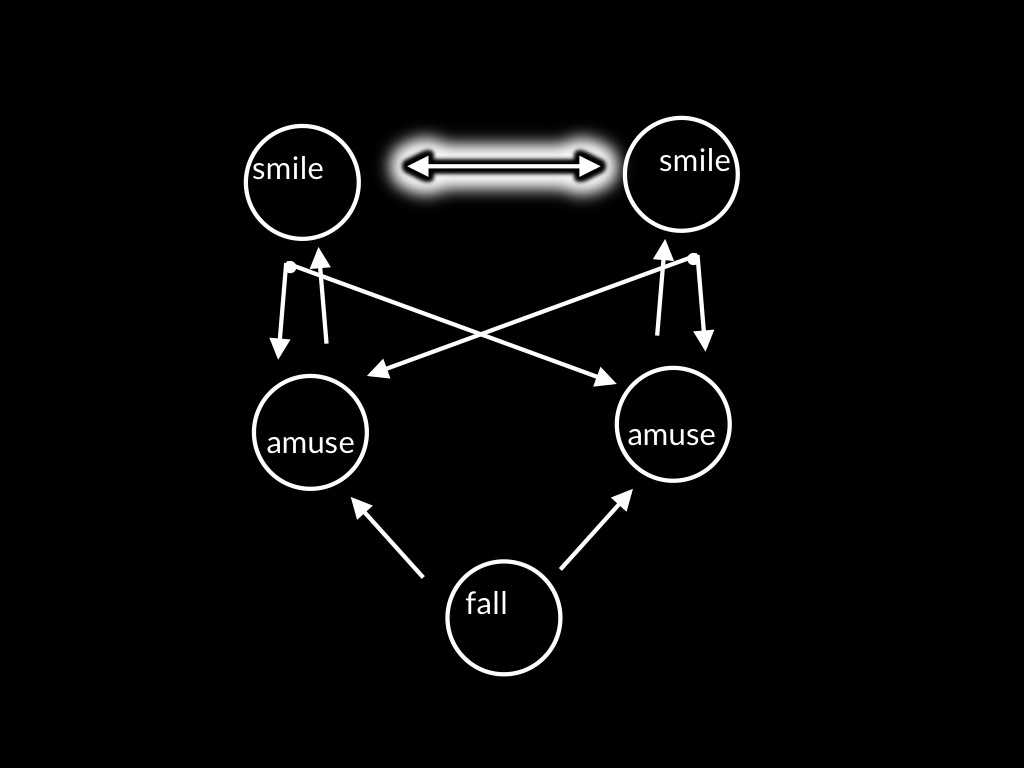

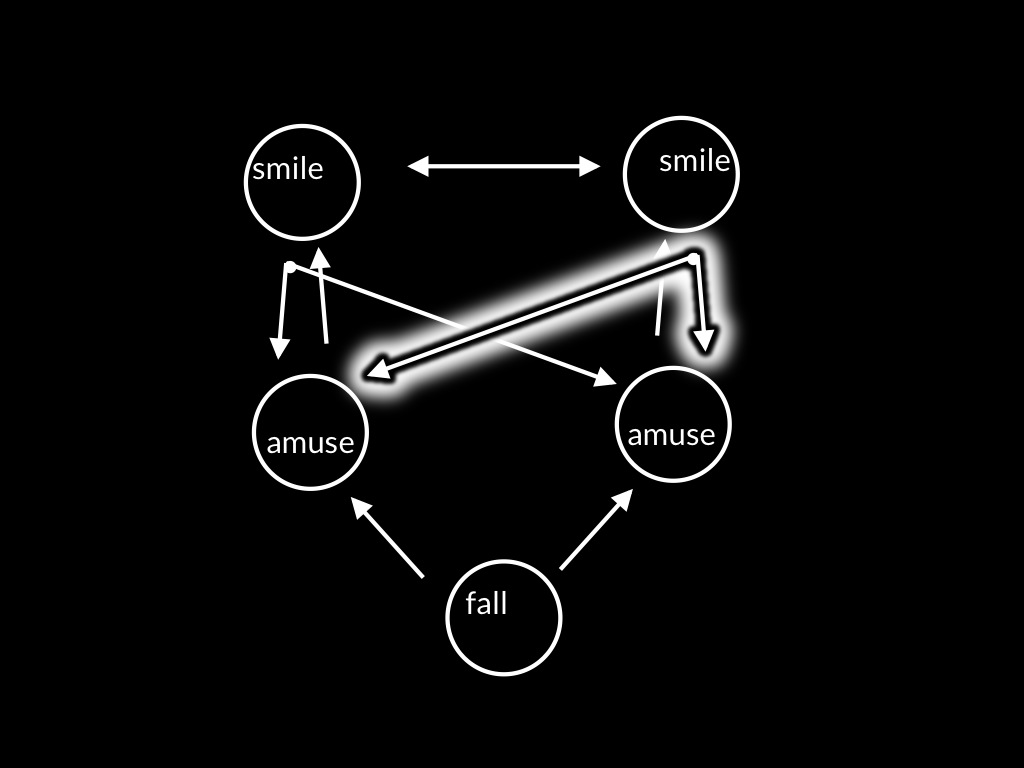

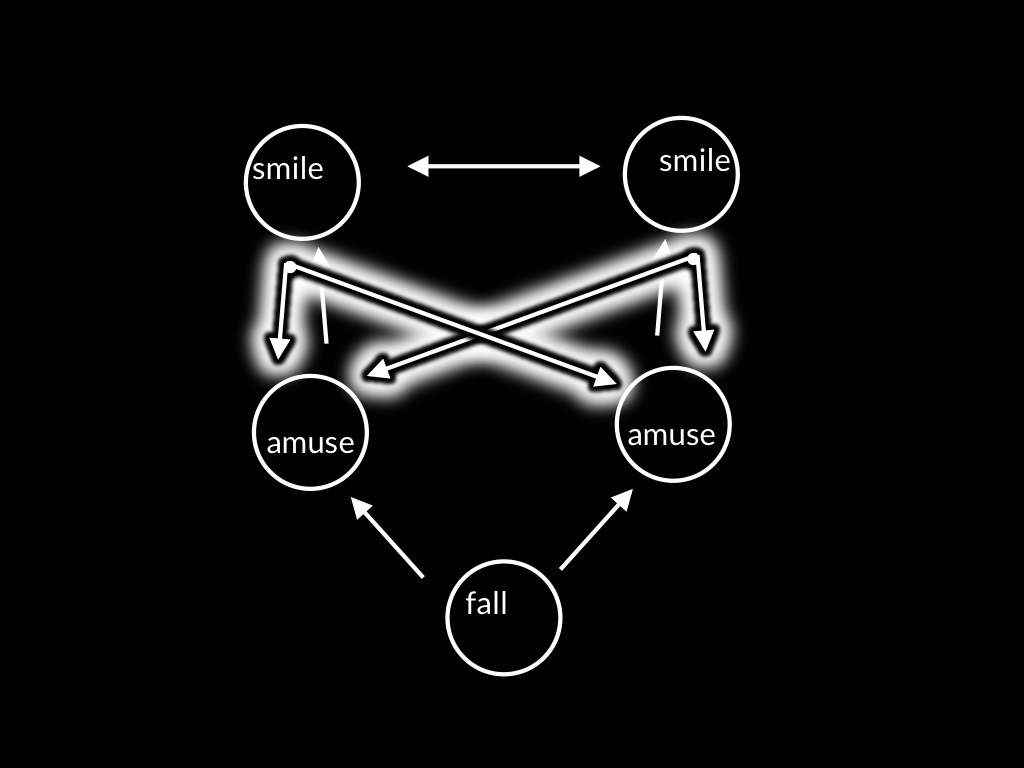

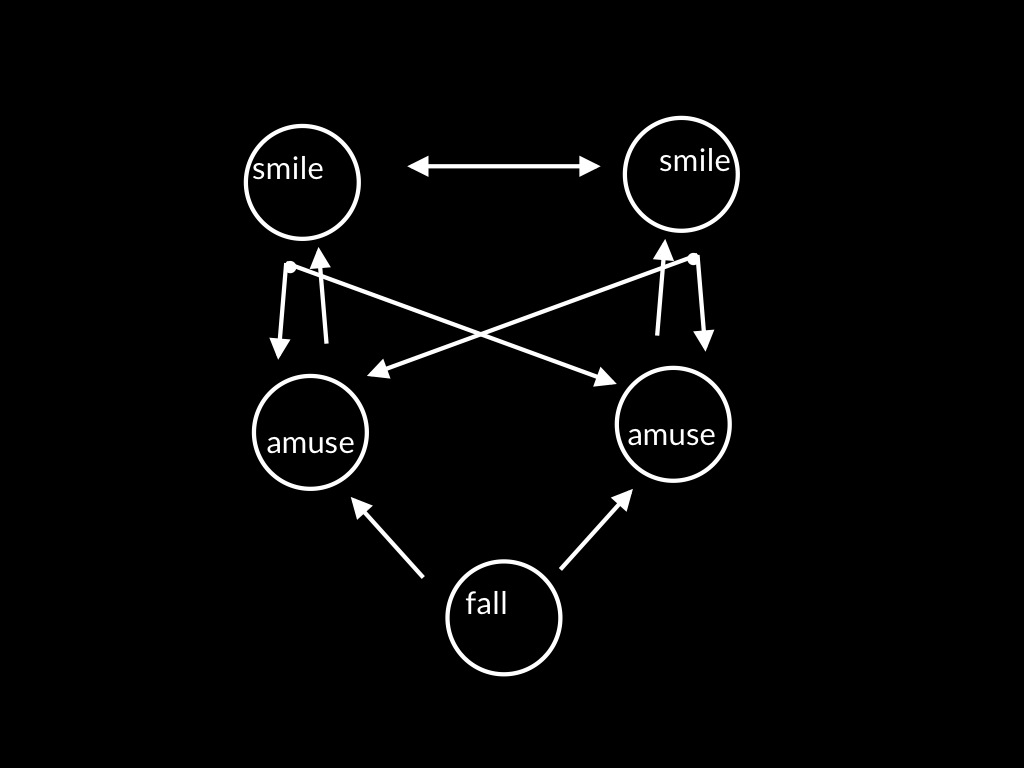

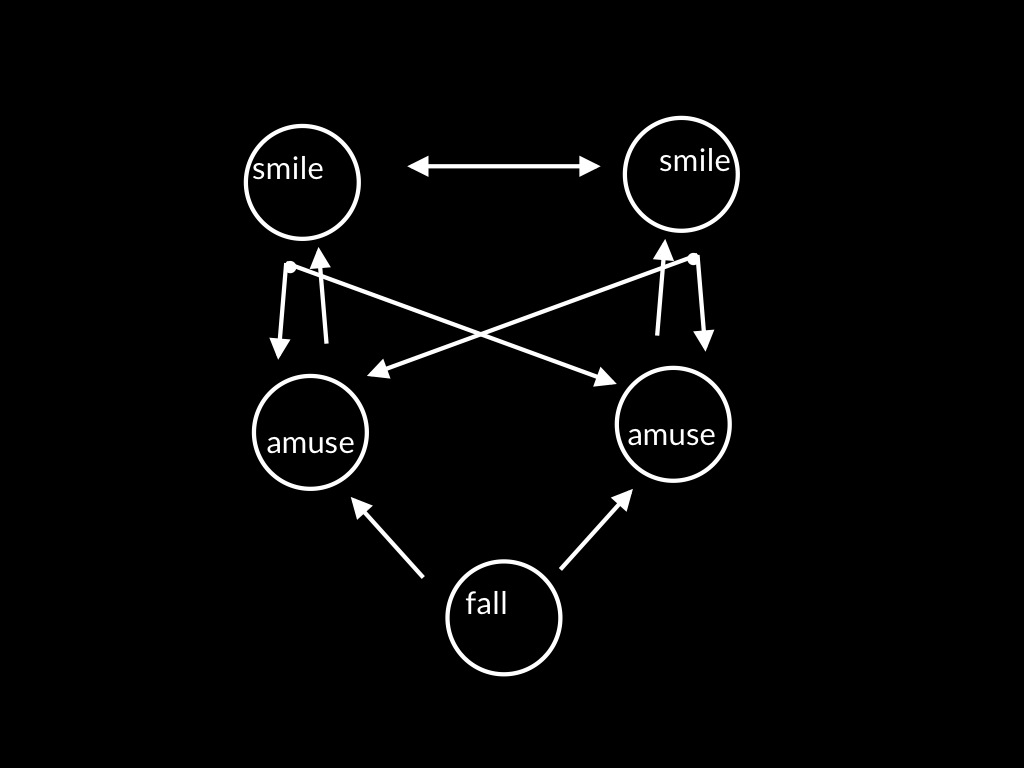

Sharing a Smile

Percepetion may yield categorical emotions (fear, surprise) and their objects. But it is probably not a way of knowing how others’ emotions are unfolding.

1. On the Intentional Stance, the outputs of social cognition are (i) propositional attitude ascriptions and (ii) action predictions.

2. Emotions unfold ...

3. ... and this is not comprehensible as a series of changes in propositional attitudes.

So: 4. Understanding the way emotions unfold is not a matter of ascribing propositional attitudes or predicting actions.

But: 5. Humans do sometimes understand how anothers’ emotions are unfolding.

So: 6. The Intentional Stance is not a fully adequate computational description of human social cognition.

How do humans ever understand how anothers’ emotions are unfolding?

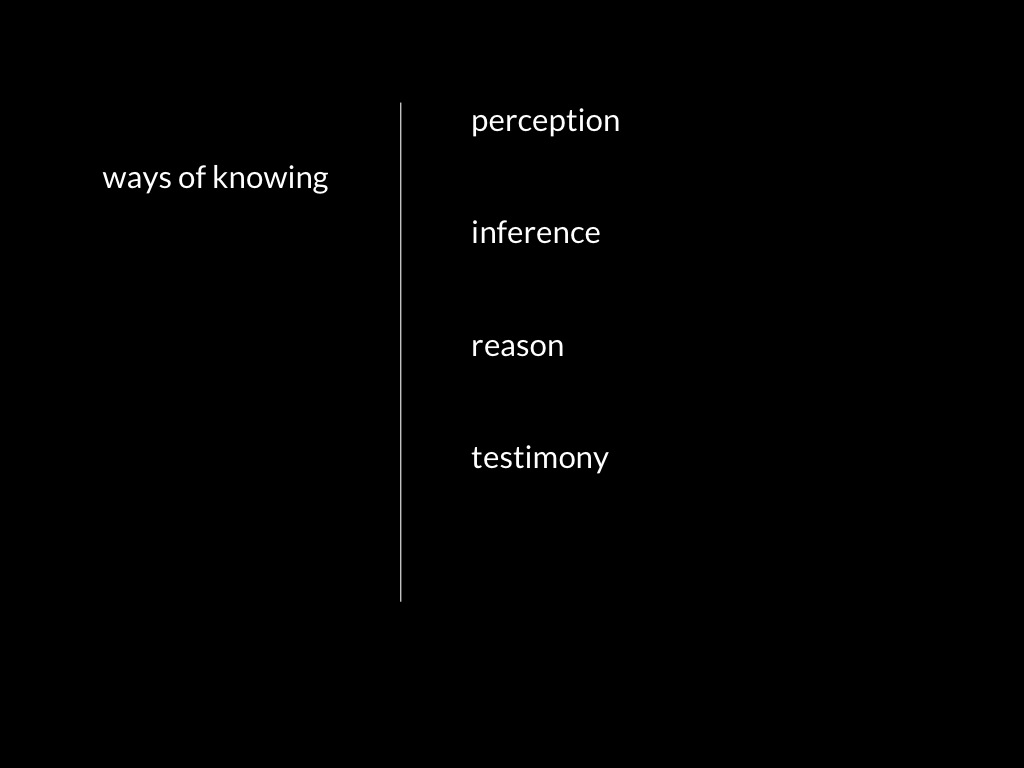

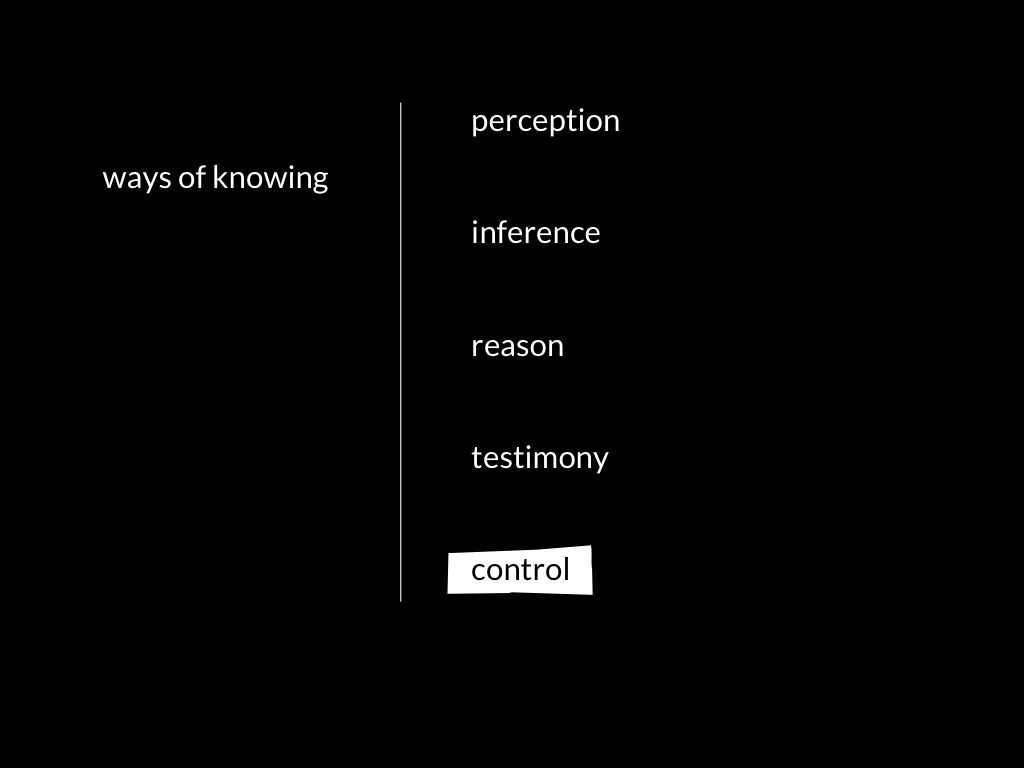

summary so far

- emotions unfold over time

- control is a way of knowing

- smiling is sometimes a goal-directed action, a goal of which is to smile a smile

Observer observes Target

control: Processes and representations in Target determine how she thinks, feels and acts.

simulation: Processes and representations occur in Observer which would occur if she were as Target is.

--- These are typically isoalted to some degree from Observer’s thought, feelings and actions.

sharing a smile: control is simulation

Are you feeling what I am feeling?

interaction takes us beyond observation:

from categories of emotion to the ways emotions unfold

Theories of radical interpretation*:

The Intentional Stance (Dennett)

Davidson’s Theory

The Teleological Stance & Your-Goal-Is-My-Goal

Minimal Theory of Mind

also an implicit theory associated with perception of emotion

control is simulation ∴ your feeling is my feeling

conclusion

1

computational descriptions

1. computational description

-- What is the thing for and how does it achieve this?

2. representations and algorithms

-- How are the inputs and outputs represented, and how is the transformation accomplished?

3. hardware implementation

-- How are the representations and algorithms physically realised?

Marr (1992, 22ff)

2

perceptually encountering mental states

Humans probably enjoy categorical perception of actions directed to the expression of particular emotions.

3

mindreading

In adult humans,

there are two (or more) distinct mindreading processes

which rely on different models of minds and actions.

4

nonhuman animals

The available evidence already justifies concluding that humans are not unique in being able to represent mental states.

5

interaction

Interacting interpreters can be in a position to know things which they would be unable to know if they were manifestly passive observers.

6

Existing attempts to provide computational descriptions (Davidson’s Radical Interpretation, Dennett’s Intentional Stance) are inadequate.

7

process architecture

The process architecture of social cognition matters ...

- perceptual processes

- automatic, nonperceptual processes

- nonautomatic, nonperceptual processes

- ...

horizontal distinction : e.g. categorical emotion vs belief-tracking

vertical distinction : e.g. automatic vs nonautomatic belief-tracking

8

fragmentation

fragmentation in the theory of radical interpretation

Dennett, Davidson

New Approach

One big theory for all social cognition.

Different theory for each kind of process.

Success : theory is coherent and descriptively adequate

Success : theory generates correct predictions

Method : pure reason

Method : signature limits

Constructing theories of radical interpretation* requires

respecting the process architecture of social cognition

and identifying testable predictions

using the method of signature limits

The domain: what is a theory of social cognition a theory of?

Social cognition:

cognition of

others’ actions and mental states

in relation to social functioning.

The question: Radical Interpretation*

How in principle could someone infer facts about actions and mental states from non-mental evidence?

What is the relation between an account of radical interpretation* and a theory of social cognition?

A theory of radical interpretation* is supposed to provide a computational description of social cognition.

the end

Theories of radical interpretation*:

The Intentional Stance (Dennett)

Davidson’s Theory

The Teleological Stance & Your-Goal-Is-My-Goal

Minimal Theory of Mind

also an implicit theory associated with perception of emotion

Davidson’s Theory of Radical Interpretation

radical interpretation*

Infer The Mind from The

The Mind: facts about actions, desires, beliefs, emotions, perspectives ...

The Evidence: facts about events and states of affairs that could be known without knowing what any particular individual believes, desires, intends, ...

Evidence:

At time t, Ayesha comes to hold ‘Sta piovendo’ true because it’s raining.

Generalisation:

Ayesha comes to hold ‘Sta piovendo’ true because it’s raining.

Assumption:

Ayesha’s beliefs are true

Conclusion:

‘Sta piovendo’ is true if and only if it’s raining.

... so when Ayesha comes to hold ‘Sta piovendo’ true, she comes to believe that it’s raining.

Why is Davidson’s a better theory?

How can it be elaborated?

--- exploit sentence structure

--- include desire

What are its limits?

--- no use for wordless targets

--- bold assumption about evidence

Objections to Davidson’s Theory of Radical Interpretation

Minds without words

Emotions unfold

1. On Radical Interpretation (and the Intentional Stance), the outputs of social cognition are (i) propositional attitude ascriptions and (ii) action predictions.

2. Emotions unfold ...

3. ... and this is not comprehensible as a series of changes in propositional attitudes.

So: 4. Understanding the way emotions unfold is not a matter of ascribing propositional attitudes or predicting actions.

But: 5. Humans do sometimes understand the way anothers’ emotions are unfolding.

So: 6. Radical Interpretation (and the Intentional Stance) is not a fully adequate computational description of human social cognition.

Indeterminacy of reference

| ordinary | contrived | |

| names | ‘Beatrice’ refers to Beatrice | ‘Beatrice’ refers to shadow-Beatrice |

| predicates | ‘... is happy’ - is true of happy things | ‘... is happy’ - is true of things that are the shadows of happy things |

‘It makes no sense, on this approach, to complain that a theory comes up with the right truth conditions time after time, but has the logical form (or deep structure) wrong. We should take the same view of reference.’

Davidson (1977, p. 223)

A dilemma about The Evidence: joint displacements or actions

‘a radical interpreter is not, at the beginning of his study, informed about any of the basic propositional attitudes of his subject.’

Davidson (1984, 17)

diagnosis

Theories of radical interpretation*:

The Intentional Stance (Dennett)

Davidson’s Theory

The Teleological Stance & Your-Goal-Is-My-Goal

Minimal Theory of Mind

also an implicit theory associated with perception of emotion

The domain: what is a theory of social cognition a theory of?

Social cognition:

cognition of

others’ actions and mental states

in relation to social functioning.

The question: Radical Interpretation*

How in principle could someone infer facts about actions and mental states from non-mental evidence?

What is the relation between an account of radical interpretation* and a theory of social cognition?

A theory of radical interpretation* is supposed to provide a computational description of social cognition.