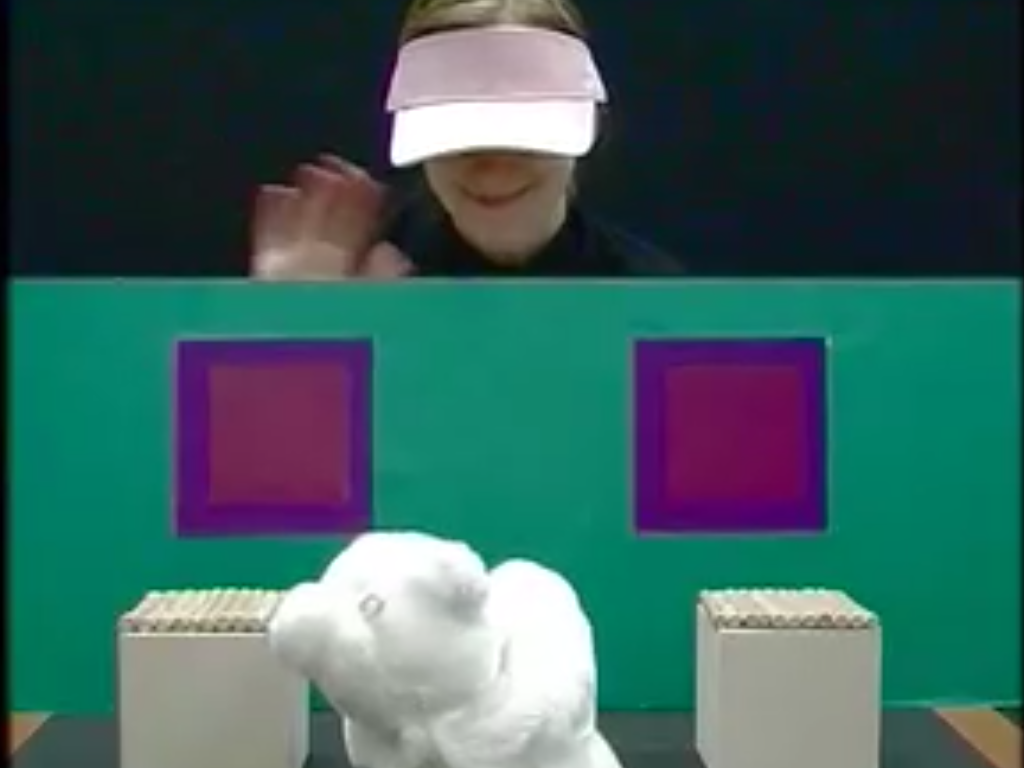

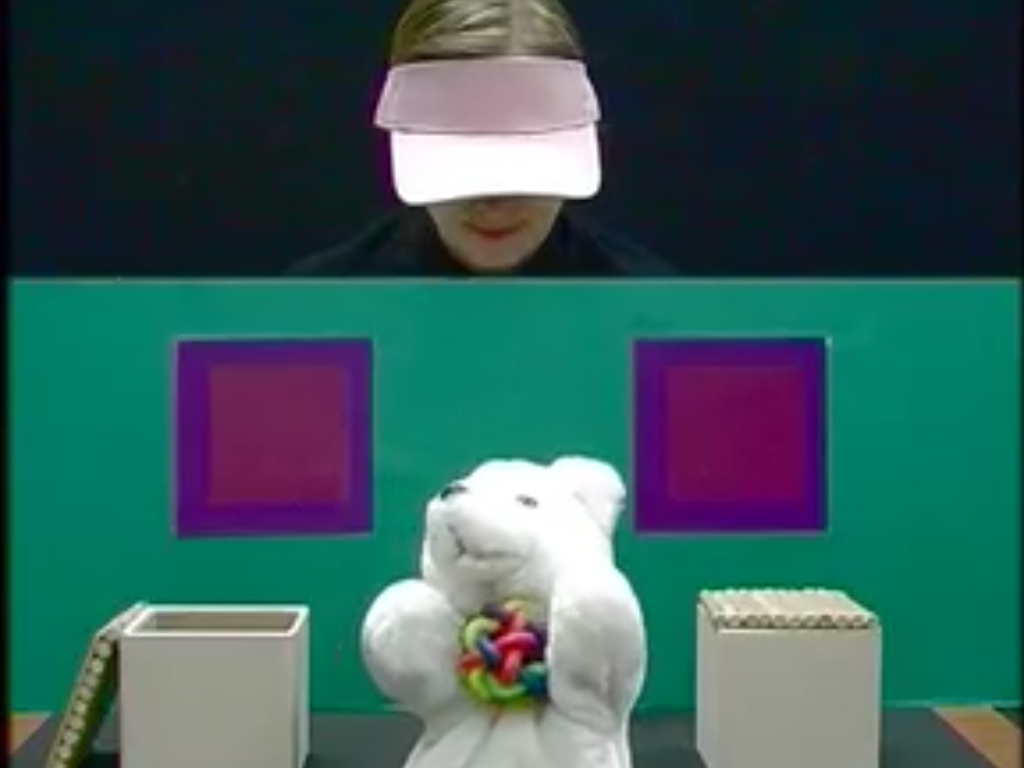

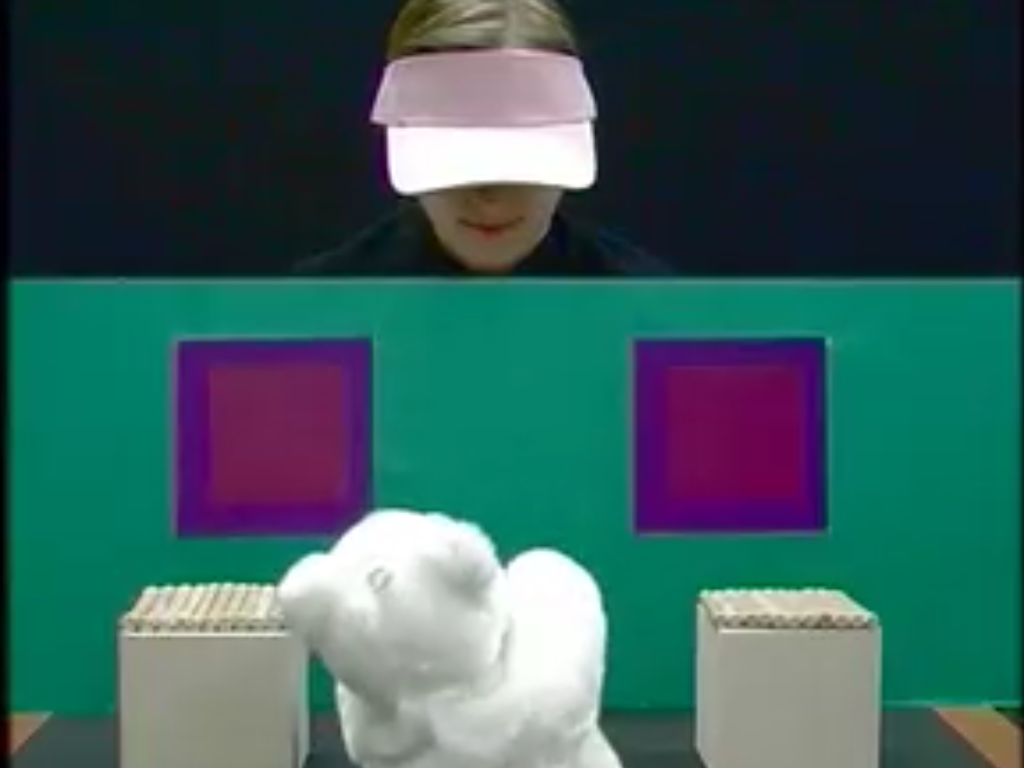

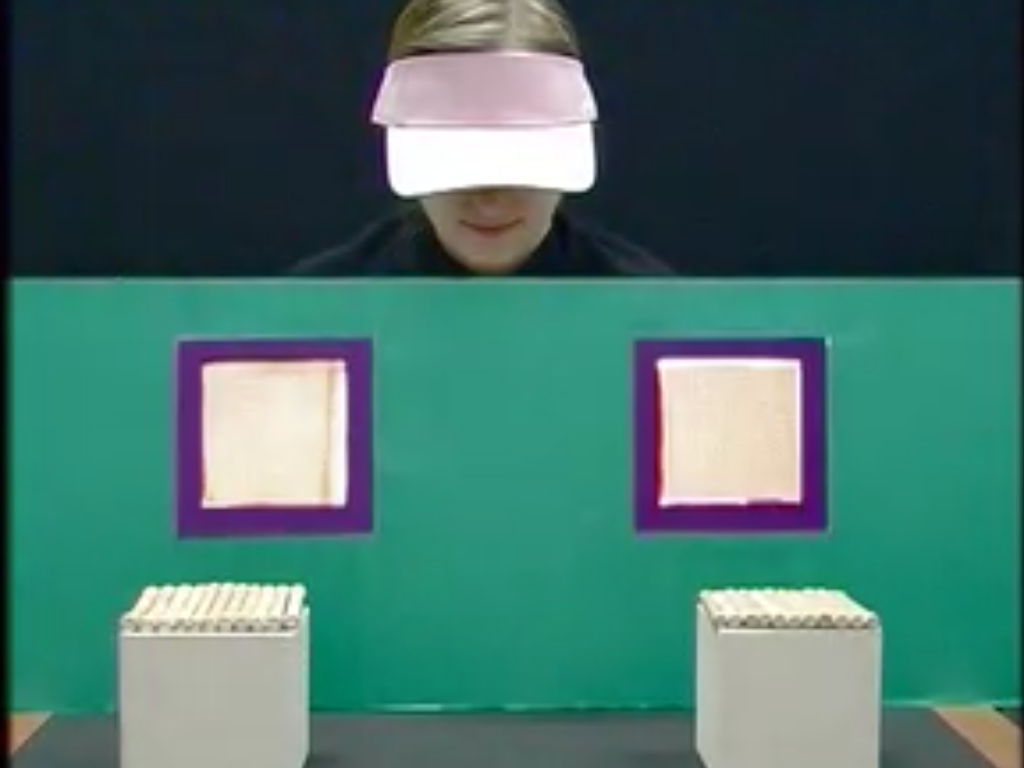

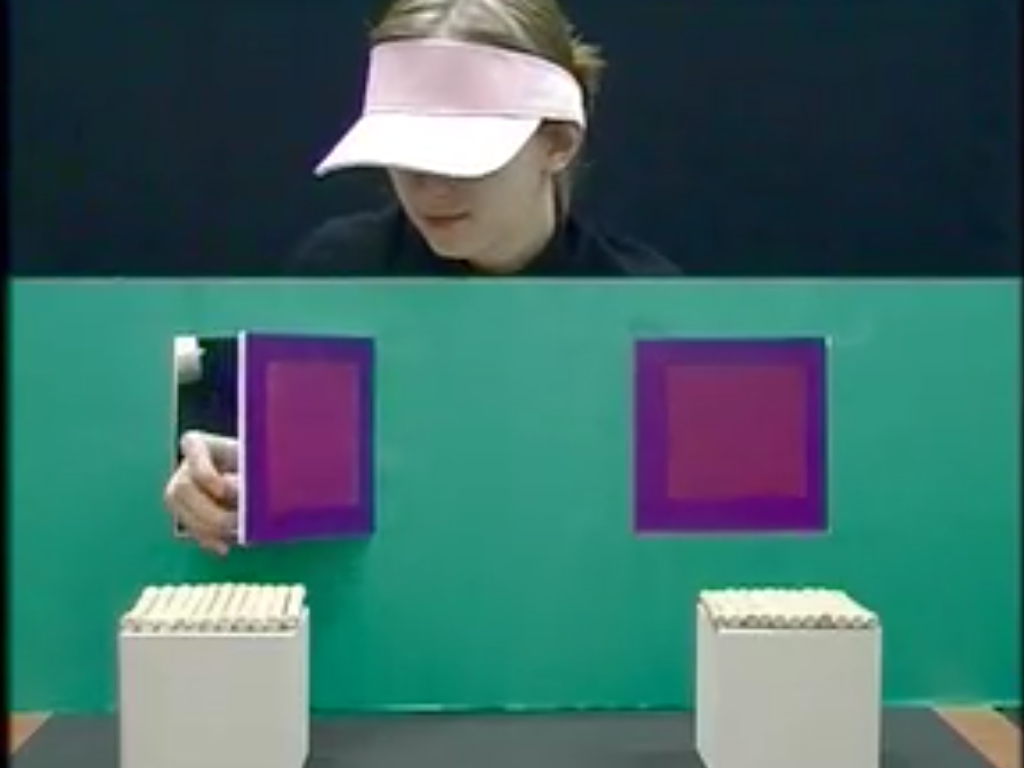

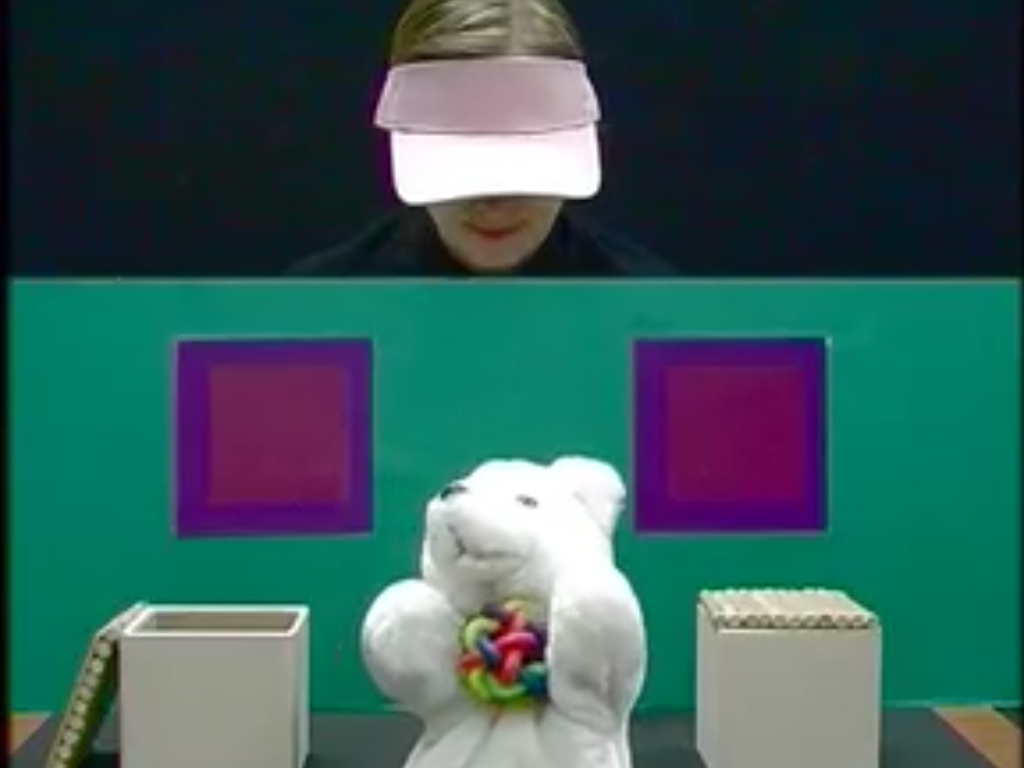

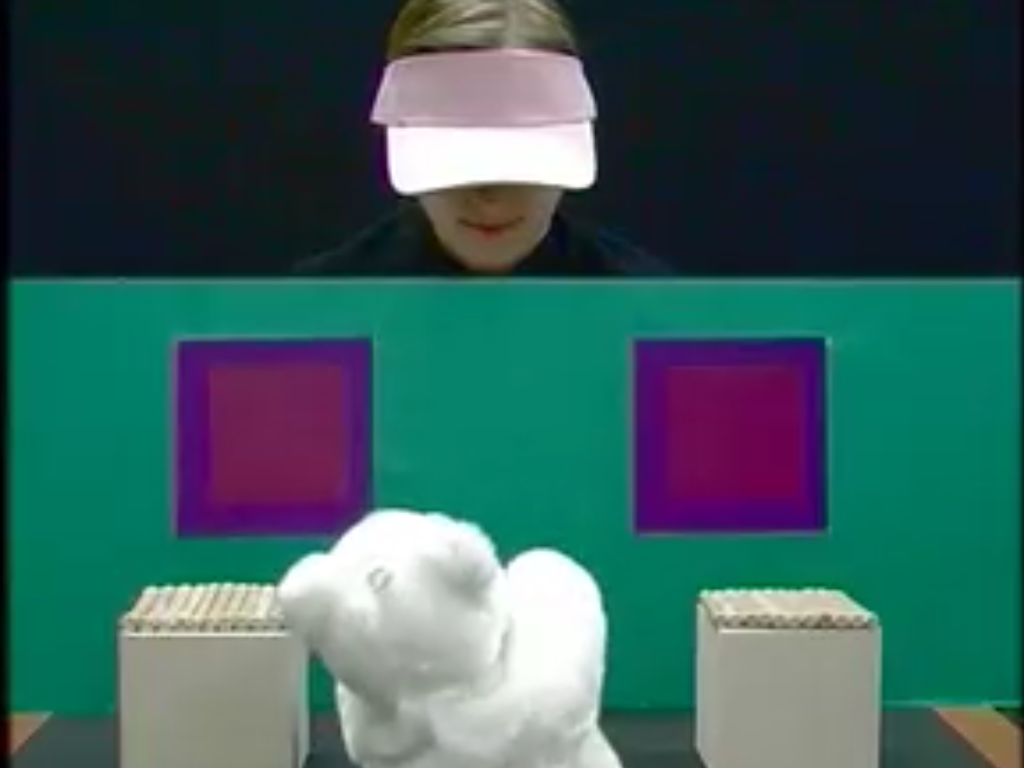

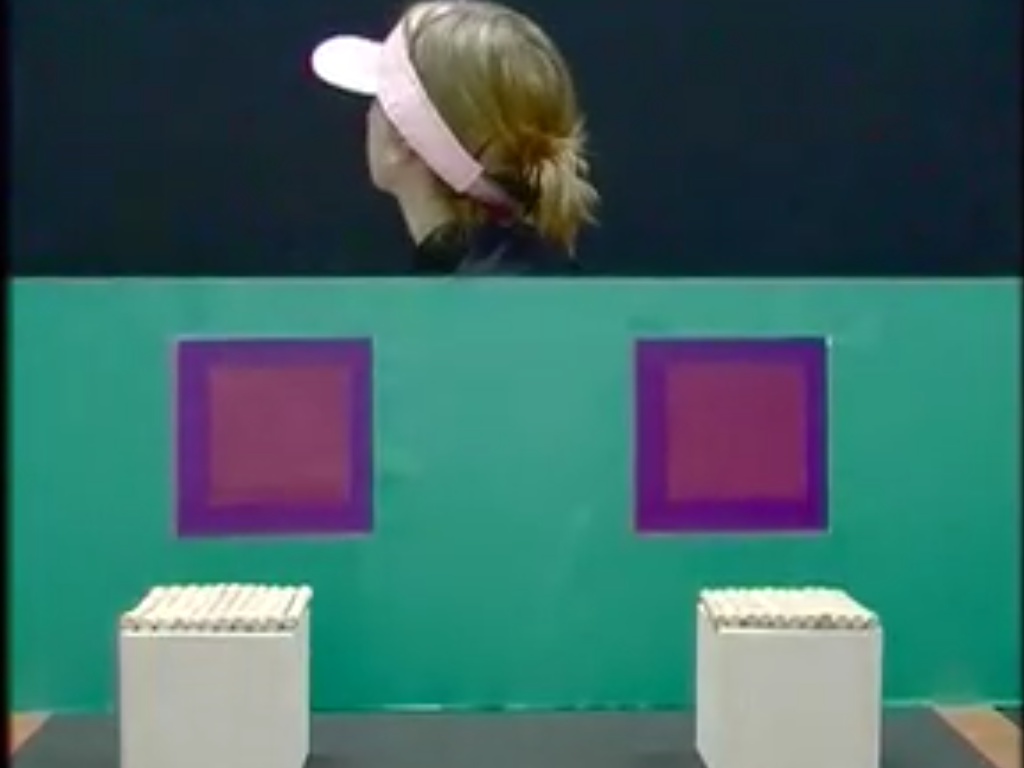

Schneider et al (2014, figure 3)

\citet{Schneider:2011fk} did just this.

They showed their participants a series of videos and instructed them to detect when a figure waved or, in a second experiment, to discriminate between high and low tones as quickly as possible.

Performing these tasks did not require tracking anyone’s beliefs, and the participants did not report mindreading when asked afterwards.

on experiment 1: ‘Participants never reported belief tracking when questioned in an open format after the experiment (“What do you think this experiment was about?”). Furthermore, this verbal debriefing about the experiment’s purpose never triggered participants to indicate that they followed the actor’s belief state’ \citep[p.~2]{Schneider:2011fk}

Nevertheless, participants’ eye movements indicated that they were tracking the beliefs of a person who happened to be in the videos.

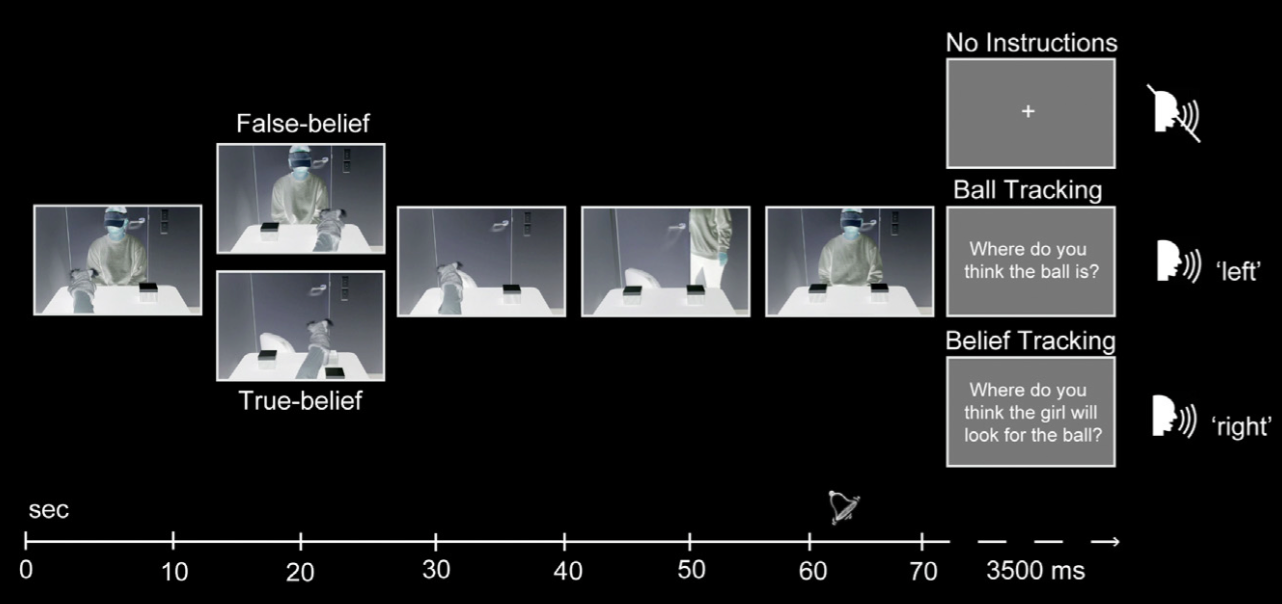

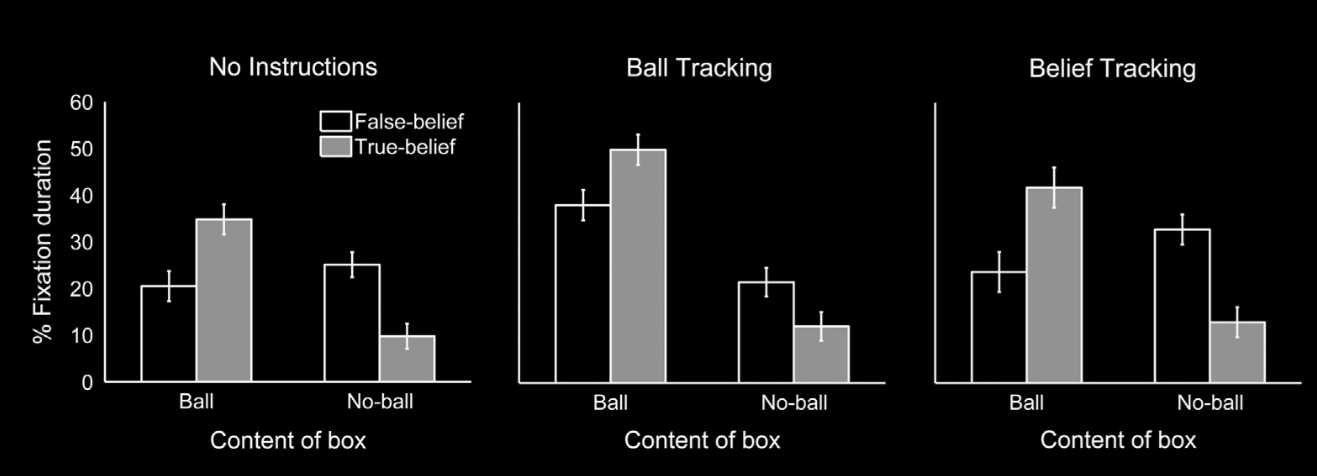

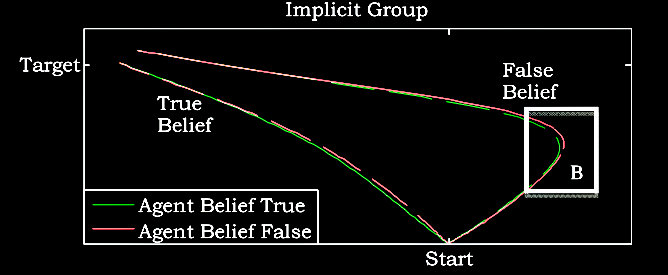

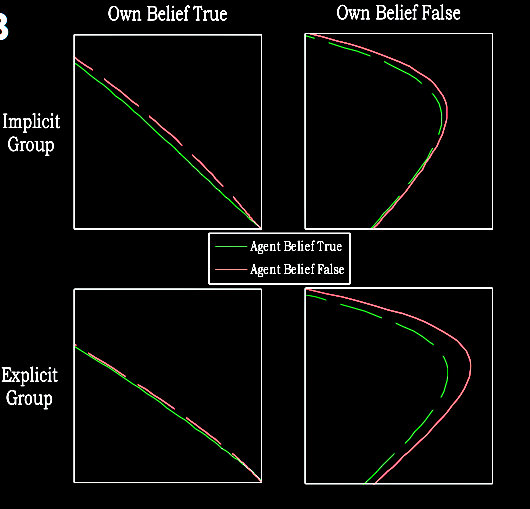

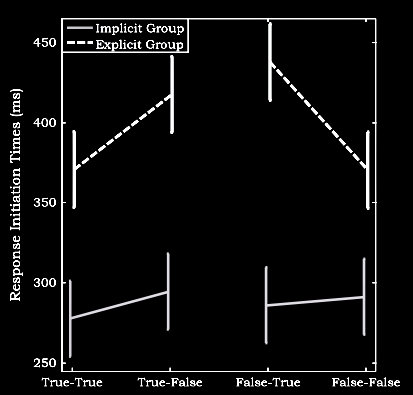

In a further study, \citet{schneider:2014_task} raised the stakes by giving participants a task that would be harder to perform if they were tracking another’s beliefs.

So now tracking another’s beliefs is not only irrelevant to performing the tasks: it may actually hinder performance.

Despite this, they found evidence in adults’ looking times that they were tracking another’s false beliefs.

This indicates that ‘subjects … track the mental states of others even when they have instructions to complete a task that is incongruent with this operation’ \citep[p.~46]{schneider:2014_task} and so provides evidence for automaticity.%

\footnote{%

% quote is necessary to qualify in the light of their interpretation; difference between looking at end (task-dependent) and at an earlier phase (task-independent)?

%\citet[p.~46]{schneider:2014_task}: ‘we have demonstrated here that subjects implicitly track the mental states of others even when they have instructions to complete a task that is incongruent with this operation. These results provide support for the hypothesis that there exists a ToM mechanism that can operate implicitly to extract belief like states of others (Apperly & Butterfill, 2009) that is immune to top-down task settings.’

It is hard to completely rule out the possibility that belief tracking is merely spontaneous rather than automatic.

I take the fact that belief tracking occurs despite plausibly making subjects’ tasks harder to perform to indicate automaticity over spontaneity.

If non-automatic belief tracking typically involves awareness of belief tracking, then the fact that subjects did not mention belief tracking when asked after the experiment about its purpose and what they were doing in it further supports the claim that belief tracking was automatic.

}

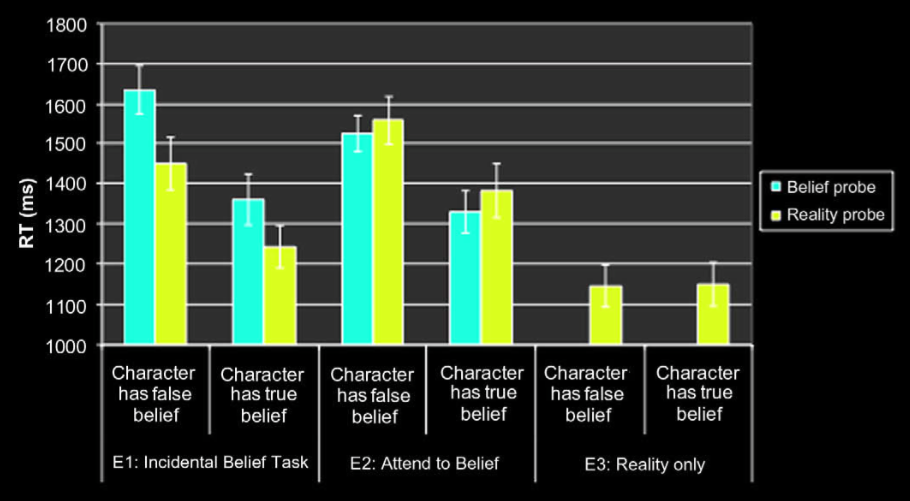

Further evidence that mindreading can occur in adults even when counterproductive has been provided by \citet{kovacs_social_2010}, who showed that another’s irrelevant beliefs about the location of an object can affect how quickly people can detect the object’s presence,

and by \citet{Wel:2013uq}, who showed that the same can influence the paths people take to reach an object.

Taken together, this is compelling evidence that mindreading in adult humans sometimes involves automatic processes only.

‘Participants never reported belief tracking when questioned in an open format after the experiment (“What do you think this experiment was about?”). Furthermore, this verbal debriefing about the experiment’s purpose never triggered participants to indicate that they followed the actor’s belief state’ \citep[p.~2]{Schneider:2011fk}