Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

A Different Approach

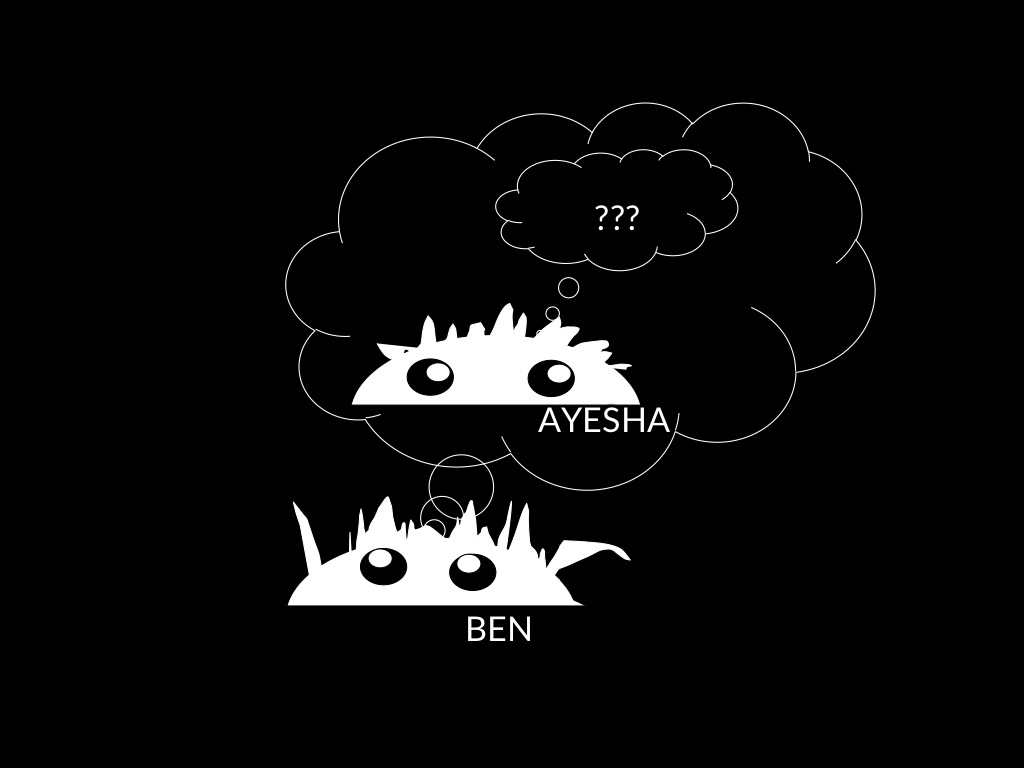

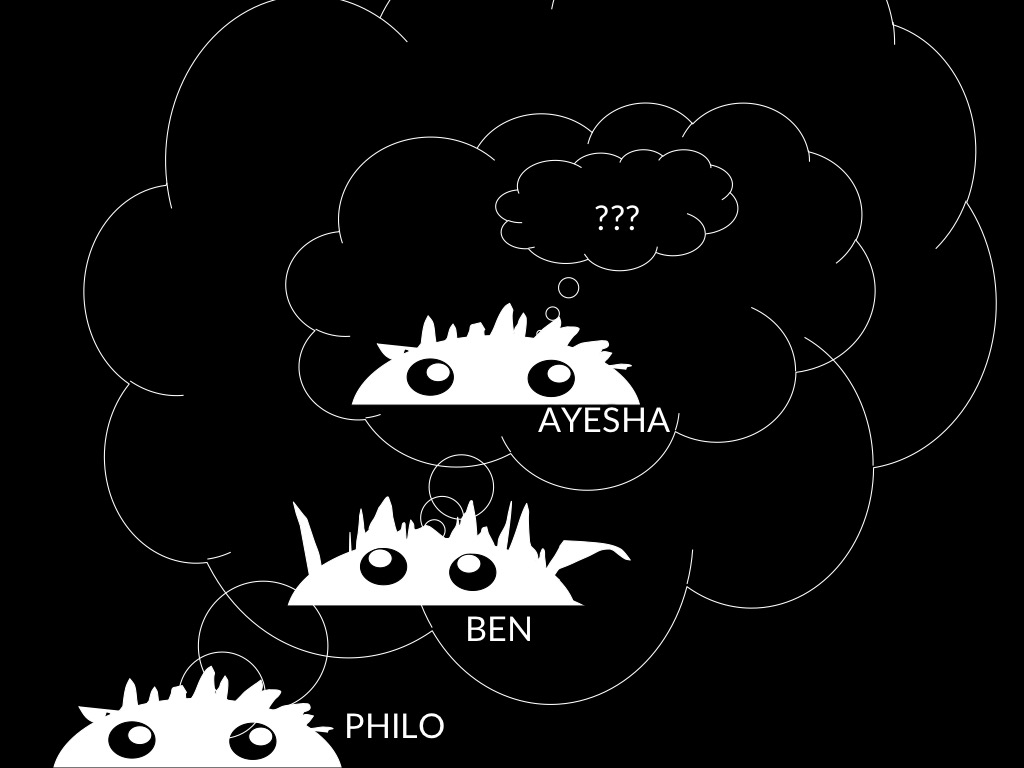

What do infants, chimps and scrub-jays reason about, or represent, that enables them, within limits, to track others’ perceptions, knowledge, beliefs and other propositional attitudes?

-- Is it mental states?

-- Or only behaviours?

What models of minds and actions, and of behaviours,

and what kinds of processes,

underpin mental state tracking in different animals?

Requirement 3: Predict Dissociations

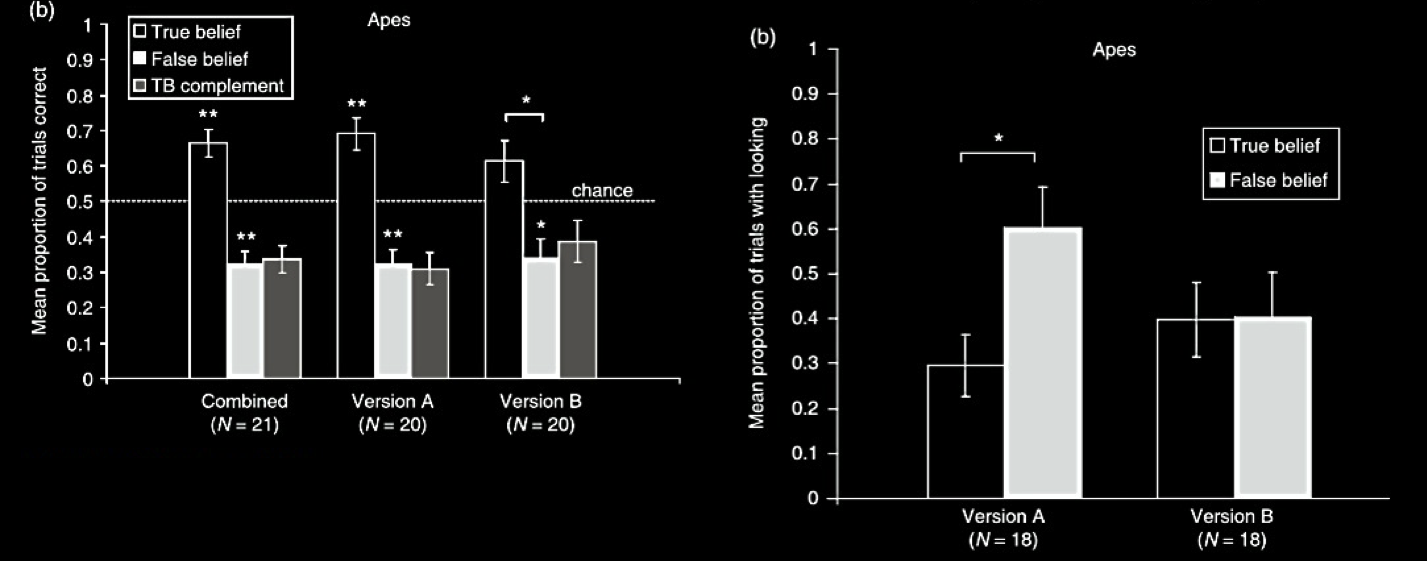

‘the present evidence may constitute an implicit understanding of belief’

Krupenye et al, 2016 p. 113

Krachun et al, 2009 figure 2 (part)

Requirement 3: Predict Dissociations

Which tasks should chimps and jays pass and fail?

Requirement 2: Models

‘chimpanzees understand … intentions … perception and knowledge,

‘chimpanzees probably do not understand others in terms of a fully human-like belief–desire psychology’

Call & Tomasello, 2008 p.~191

Requirement 2: Models

How do chimps or jays variously model minds and actions?

‘Nonhumans represent mental states’ is not a hypothesis

‘the core theoretical problem in contemporary research on animal mindreading is that the bar—the conception of mindreading that dominates the field—is too low, or more specifically, that it is too underspecified to allow effective communication among researchers, and reliable identification of evolutionary precursors of human mindreading through observation and experiment’

Heyes, 2014, p. 318

Requirement 2: Models

Requirement 1: Diversity in Strategies

Requirement:

We can distinguish,

both within an individual

and between individuals,

mindreading which involves representing mental states

from

mindreading which does not.

Three Requirements

1. Diversity in Strategies

2. Models

3. Predict Dissociations

What models of minds and actions, and of behaviours,

and what kinds of processes,

underpin mental state tracking in different animals?

Way forward:

1. Construct a theory of behaviour reading

2. Construct a theory of mindreading