Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Some Evidence

Hare et al (2001, figure 1)

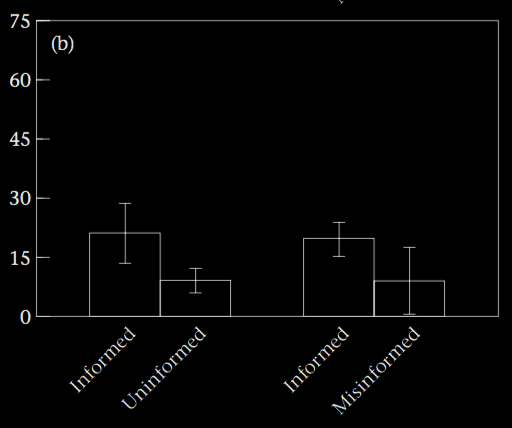

Hare et al (2001, figure 2b)

‘subordinate subjects retrieved a significantly larger percentage of food when dominants lacked accurate information about the location of food

‘(Wilcoxon test: Uninformed versus Control Uninformed: T=36, N=8, P<0.01; Misinformed versus Control Misinformed: T=36, N=8, P<0.01)’

Hare et al (2001, p. 143)

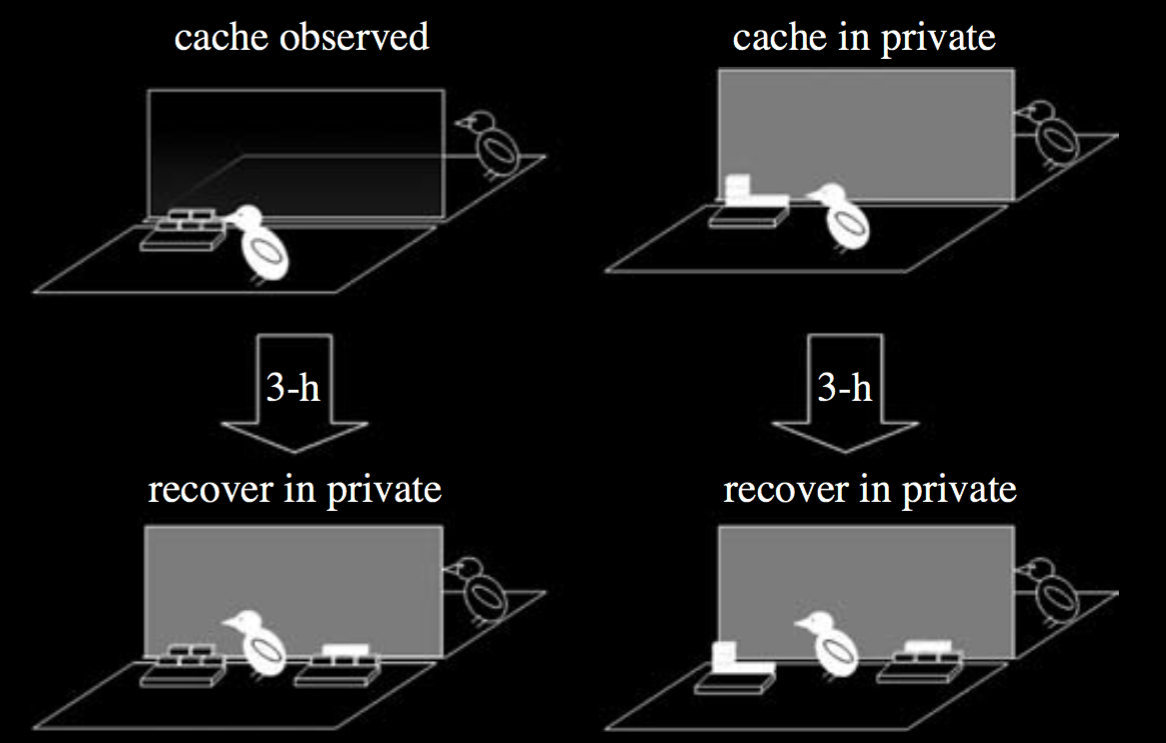

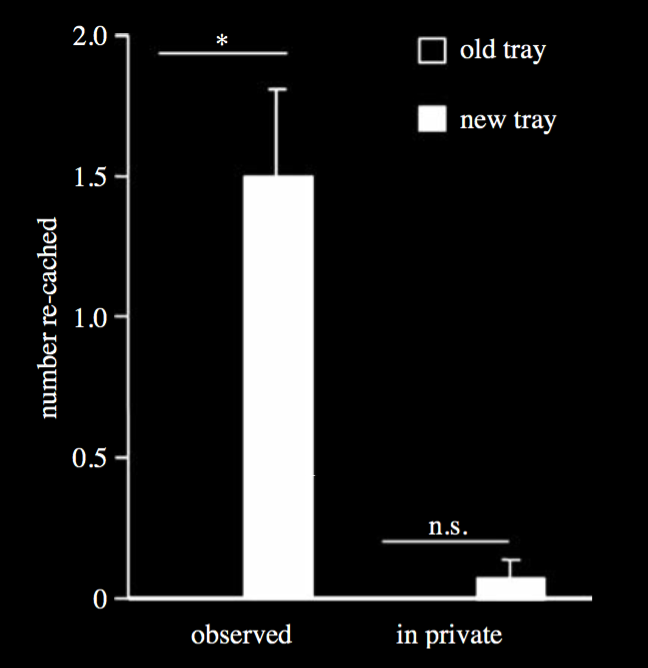

Clayton et al, 2007 figure 11

Clayton et al, 2007 figure 12

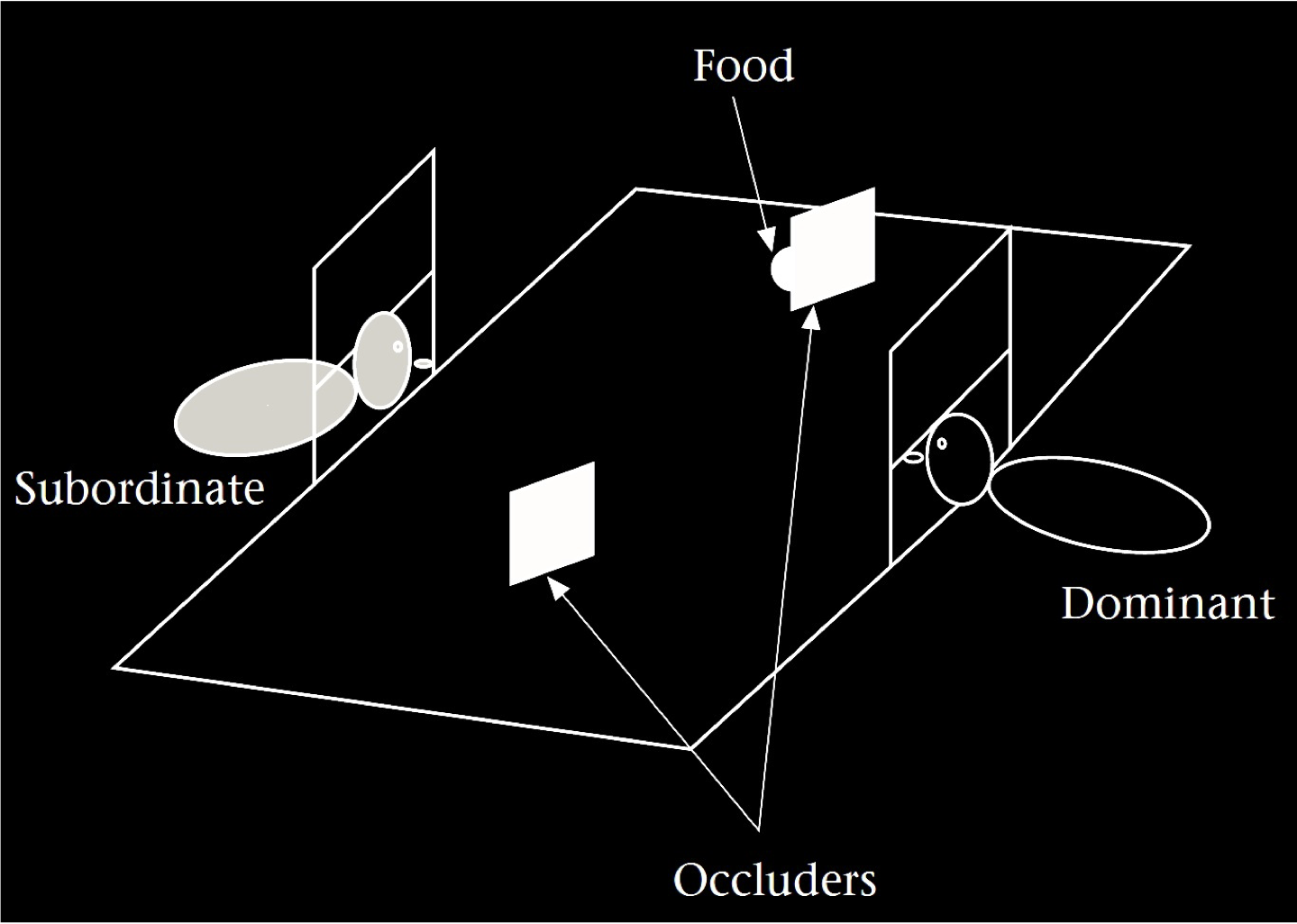

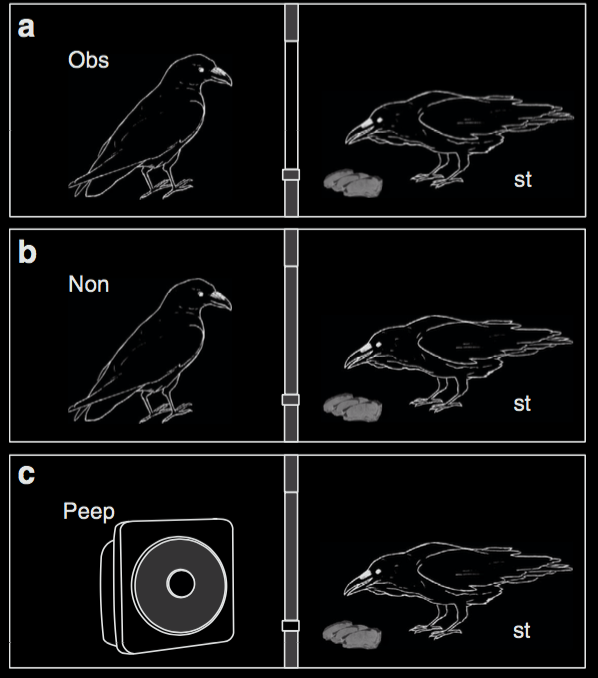

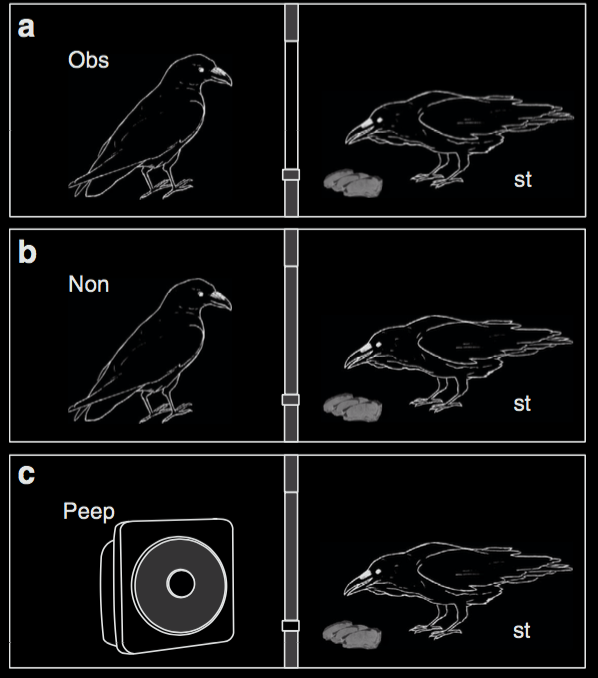

Bugnyar et al, 2016 figure 1

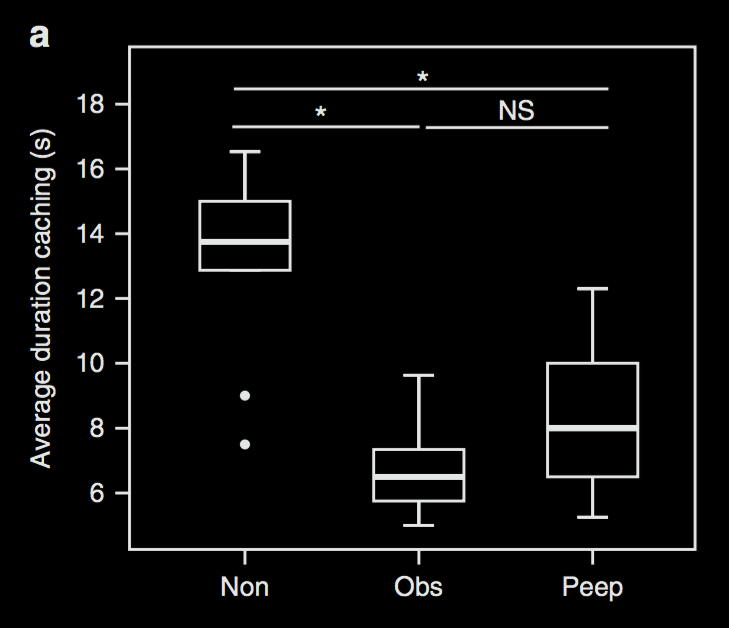

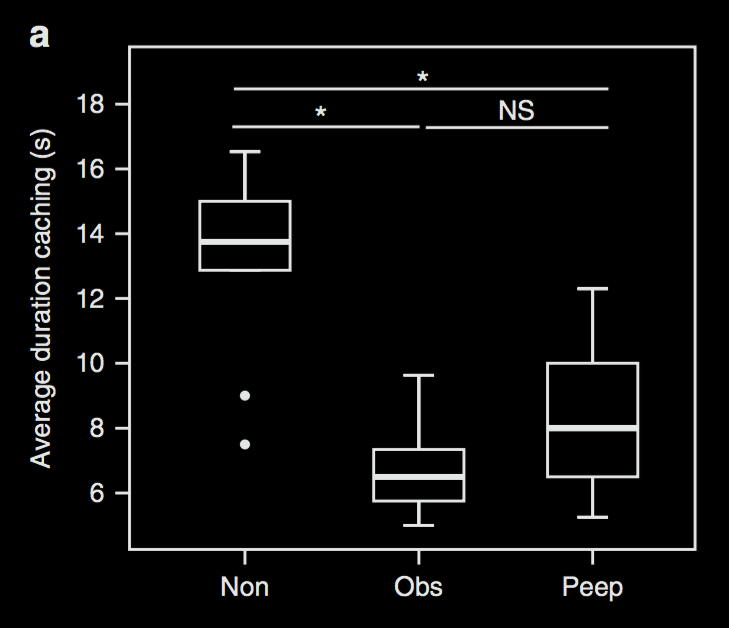

Bugnyar et al, 2016 figure 2a

Bugnyar et al, 2016 figure 1